The health effects of climate change

March 20, 2017

By Lise Van Susteren, MD

“Exercising my ‘reasoned judgment,’ I have no doubt that the right to a climate system capable of sustaining human life is fundamental to a free and ordered society.” – U.S. District Judge Ann Aiken in Kelsey Cascadia Rose Juliana vs. United States of America, et al.

In many areas of the world, the simple act of breathing has become hazardous to people’s health. According to the World Health Organization, more people die every day from air pollution than from HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and road injuries combined. In China, more than 1 million deaths annually are linked to polluted air (76/100,000); in India the number of deaths is more than 600,000 annually (49/100,000); and in the United States, that figure comes to more than 38,000 (12/100,000).

Unhealthy air is primarily the result of burning “fossil fuels” – coal, oil, and gas – for energy, a deadly practice. It fills the air with harmful particulate matter that we breathe in, and it alters the chemistry of our atmosphere by releasing CO2, the heat-trapping greenhouse gas responsible for global climate instability.

And yet, non-polluting, alternative options – such as sun and wind power – are readily available.

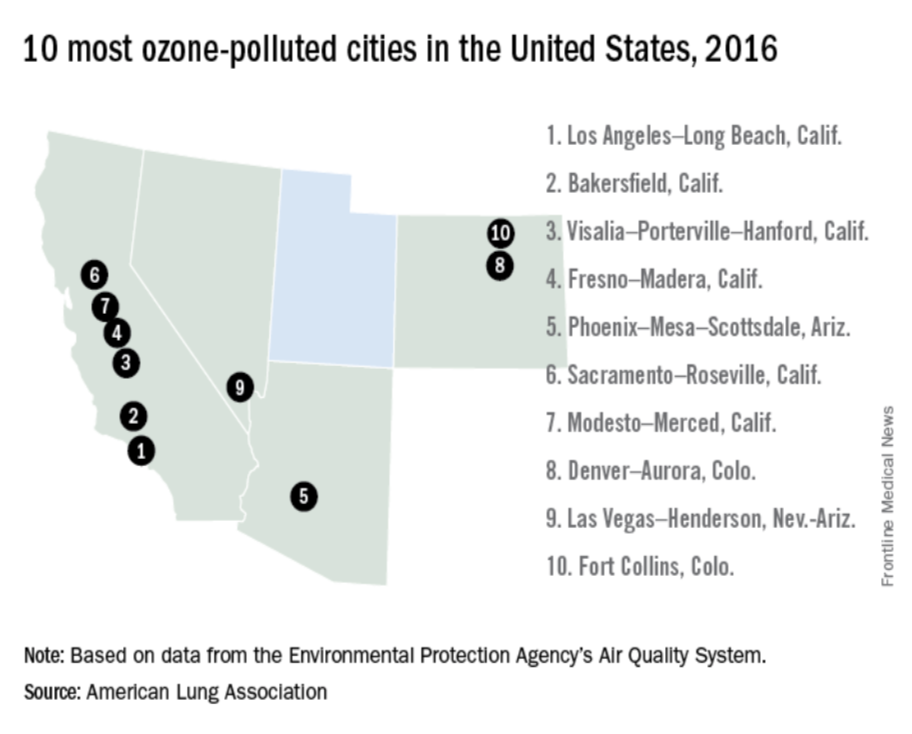

Dirty air is visible on a hot summer day – when, mixed with other substances, it forms smog. Higher temperatures can then speed up the chemical reactions that form smog. We breathe in that polluted air, especially on days when the air is stagnant or there is temperature inversion.

The health effects of climate change

Black carbon found in air pollution leads to drug-resistant bacteria and alters antibiotic tolerance.1 The pollution also is associated with multiple cancers: lung, liver, ovarian, and, possibly, breast.2,3,4,5 It causes inflammation linked to the development of coronary artery disease (seen even in children!) and plaque formation leading to heart attacks and cardiac arrhythmias – including atrial fibrillation. Air pollution causes, triggers, or worsens respiratory illnesses – chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema, asthma, infections – and is responsible for lifelong diminished lung volume in children (a reason families are leaving Beijing.) Exponentially increased rates of autism are linked to bad air quality, as are autoimmune diseases, which also are on the rise.6,7 Polluted air causes brain inflammation – living near sources of air pollution increases the risk of dementia – and other neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.8

The blood brain barrier protects the brain from most foreign matter, but particulate matter, especially ultrafine particulate matter of less than 1 mcm such as magnetite, can cross directly into the brain via the olfactory nerve. (Magnetite has been identified in the brain tissue of residents living in areas where the substance is produced as a result of industrial waste.) While particulate matter of 2.5 mcmis measured in the United States, ultrafine particulate matter is not.

Psychiatric symptoms and chronic psychiatric disorders also are associated with polluted air: On days with poor air quality, a statistically significant increase is seen in suicide threats and visits to emergency departments for panic attacks.9,10

A rise in aggression occurs when there are abnormally high temperatures and significant changes in rainfall. More assaults, murders, suicides, domestic violence, and child abuse can be expected, and a rise in unrest around the world should come as no surprise.

As a consequence of increased CO2 in the atmosphere, temperatures have already risen by 2° F: Sixteen of the hottest years on record have occurred in the last 17 years, with 2016 as the hottest year ever recorded. In Iraq and Kuwait, the temperature last summer reached 129.2° F.

We are experiencing more frequent and extreme weather events, chronic climate conditions, and the cascading disruption of ecosystems. Drought and sea level rise are leading to physical and psychological impacts – both direct and indirect. Some regions of the world have become destabilized, triggering migrations and the refugee crisis.

Along with these psychological impacts, CO2 affects cognition: A recent study by the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, shows that the indoor levels of CO2 to which American workers typically are exposed impair cognitive functioning, particularly in the areas of strategic thinking, information processing, and crisis management.11

What do we do about it?

As mental health professionals, we know that aggression can be overt or passive (from inaction). Overwhelming evidence shows harm to public health from burning fossil fuels, and yet, though we are making progress, resistance still exists in the transition to clean, renewable energy critical for the health of our families and communities. When political will is what stands between us and getting back on a path to breathing clean air, how can inaction be understood as anything but an act of aggression?

This issue has reached U.S. courts: In a landmark case, 21 youths aged 9-20 years represented by “Our Children’s Trust” are suing the U.S. government in the Oregon U.S. District Court for failure to act on climate. The case, heard by Judge Ann Aiken, is now headed to trial.

All of us have a duty to collectively, repeatedly, and forcefully call on policy makers to take action.

That leads me to what we can do as doctors. In this effort to quickly transition to safe, clean renewable energy, we all have a role to play. The notion that we can’t do anything as individuals is no more credible than saying “my vote doesn’t matter.” Just as our actions as voters in a democracy demonstrate the collective civic responsibility we owe one another, so too do our actions on climate. As global citizens, all actions that we take to help us live within the planet’s means are opportunities to restore balance.

What we do collectively drives markets and determines the social norms that powerfully influence the decisions of others – sometimes even unconsciously.

As doctors, we have a unique role to play in the places we work – urging hospitals, clinics, academic centers, and other organizations and facilities to lead by example, become role models for energy efficiency, and choose clean renewable energy sources over the ones harming our health. We can start by choosing wind and solar to power our homes and influencing others to do the same.

We are the voices because this is a health message.

Dr. Van Susteren. MD, is a practicing general and forensic psychiatrist in Washington, DC. She serves on the advisory board of the Center for Health and the Global Environment at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, Boston. Dr. Van Susteren is coauthor of the report, “The Psychological Effects of Global Warming on the United States – Why the U.S. Mental Health System is Not Prepared.”

References

1. Environ Microbiol. 2017 Feb 14. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13686. 2. Environ Health Perspect. 2017 Mar;125[3]:378-84. 3. J Hepatol. 2015;63[6]:1397-1404. 4. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2012;75[3]:174-82. 5. Environ Health Perspect. 2012 Nov; 118[11]:1578-83. 6. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2016; 57[3]:271-92. 7. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010;22[2]219-25. 8. Inhal Toxicol. 2008;20[5]:499-506. 9. J Psychiatr Res. 2015 Mar;62:130-5. 10. Schizophr Res. 2016 Oct 5. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.10.003. 11. Environ Health Perspect. 2016 Jun;124[6]:805-12.